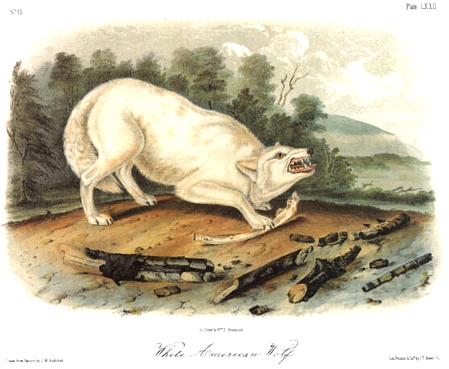

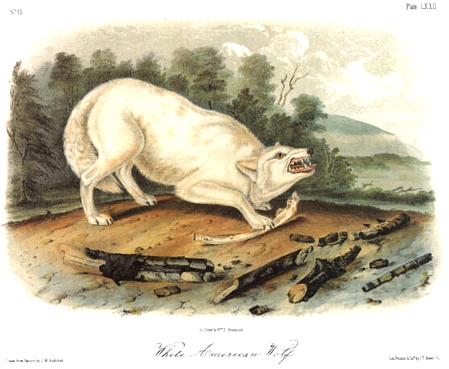

72 White American Wolf

CANIS LUPUS.--Linn.--(VAR. ALBUS.)

WHITE AMERICAN WOLF.

[Gray Wolf (color phase). ENDANGERED]

PLATE LXXII--MALE.

C. magnitudine formaque C. lupi; vellere flavido-albo; naso canescente.

CHARACTERS.

Size and shape of the grey wolf, fur over the whole body of a

yellowish-white colour, with a slight tinge of grey on the nose.

SYNONYMES.

WHITE WOLF, Lewis and Clark, vol. i., p. 107, vol. iii., p. 263.

CANIS LUPUS, Albus, Sabine, Frank. Journ., p. 652.

WHITE WOLF, Frank. Journal, p. 312.

WHITE WOLF, Lyon's Private Journal, p. 279.

LUPUS ALBUS VAR. B. WHITE WOLF, Richardson, F. B. A., p. 68.

DESCRIPTION.

In shape, this Wolf resembles all the other varieties of large North

American Wolves. (The prairie or barking Wolf, a distinct and different

species, excepted.) It is large, stout, and compactly built; the canine teeth

are long; others stout, large, rather short. Eyes, small. Ears, short and

triangular. Feet, stout. Nails, strong and trenchant. Tail, long and bushy.

Hairs on the body, of two kinds; the under coat composed of short, soft and

woolly hair, interspersed with longer coarse hair five inches in length. The

hairs on the head and legs are short and smooth, having none of the woolly

appearance of those on other portions of the body.

COLOUR.

The short fur beneath the long white coat, yellowish white, the whole outer

surface white, there is a slight tinge of greyish on the nose. Nails black;

teeth white.

Another Specimen.--Snow-white on every part of the body except the tail,

which is slightly tipped with black.

Another.--Light grey on the sides legs and tail; a dark brown stripe on the

back, through which many white hairs protrude, giving it the appearance of being

spotted with brown and white. This variety resembles the young Wolf noticed by

RICHARDSON, (p. 68) which he denominates the pied Wolf.

DIMENSIONS.

Feet. Inches.

From point of nose to root of tail, . . . . . . . 4 6

From tail, vertebrae,. . . . . . . . . . . . 1 2

From tail, end of hair, . . . . . . . . . . . 1 8

Height of ear, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 1/2

HABITS.

The White Wolf is far the most common variety of the Wolf tribe to be met

with around Fort Union, on the prairies, and on the plains bordering the Yellow

Stone river. When we first reached Fort Union we found Wolves in great

abundance, of several different colours, white, grey, and brindled. A good many

were shot from the walls during our residence there, by EDWARD HARRIS, Esq., and

Mr. J. G. BELL. We arrived at this post on the 12th of June, and although it

might be supposed at that season the Wolves could procure food with ease, they

seemed to be enticed to the vicinity of the Fort by the cravings of hunger. One

day soon after our arrival, Mr. CULBERTSON told us that if a Wolf made its

appearance on the prairie, near the Fort, he would give chase to it on

horseback, and bring it to us alive or dead. Shortly after, a Wolf coming in

view, he had his horse saddled and brought up, but in the meantime the Wolf

became frightened and began to make off, and we thought Mr. CULBERTSON would

never succeed in capturing him. We waited, however, with our companions on the

platform inside the walls, with our heads only projecting above the pickets, to

observe the result. In a few moments we saw Mr. CULBERTSON on his prancing

steed as he rode out of the gate of the Fort with gun in hand, attired only in

his shirt, breeches and boots. He put spurs to his horse and went off with the

swiftness of a jockey bent upon winning a race. The Wolf trotted on and every

now and then stopped to gaze at the horse and his rider, but soon finding that

be could no longer indulge his curiosity with safety, he suddenly gallopped off

with all his speed, but he was too late in taking the alarm, and the gallant

steed soon began to gain on the poor cur, as we saw the horse rapidly shorten

the distance between the Wolf and his enemy. Mr. CULBERTSON fired off his gun

as a signal to us that he felt sure of bringing in the beast, and although the

hills were gained by the fugitive, he had not time to make for the broken ground

and deep ravines, which he would have reached in few minutes, when we heard the

crack of the gun again, and Mr. CULBERTSON galloping along dexterously picked up

the slain Wolf without dismounting from his horse, threw him across the pummel

of his saddle, wheeled round and rode back to the Fort, as fast as he had gone

forth, a hard shower of rain being an additional motive for quickening his pace,

and triumphantly placed the trophy of his chase at our disposal. The time

occupied, from the start of the hunter, until his return with his prize did not

exceed twenty minutes. The jaws of the animal had become fixed, and it was

quite dead. Its teeth had scarified one of Mr. CULBERTSON's fingers

considerably, but we were assured that this was of no importance, and that such

feats as the capture of this wolf were so very common, that no one considered it

worthy of being called an exploit.

Immediately after this real wolf hunt, a sham Buffalo chase took place, a

prize of a suit of clothes being provided for the rider who should load and

shoot the greatest number of times in a given distance. The horses were

mounted, and the riders started with their guns empty--loaded in a trice, while

at speed, and fired first on one side and then on the other, as if after

Buffaloes. Mr. CULBERTSON fired eleven times in less than half a mile's run,

the others fired less rapidly, and one of them snapped several times, but as a

snap never brings down a Buffalo, these mishaps did not count. We were all well

pleased to see these feats performed with much ease and grace. None of the

riders were thrown, although they suffered their bridles to drop on their horses

necks, and plied the whip all the time. Mr. CULBERTSON's mare, which was of the

full, black foot Indian breed, about five years old, was highly valued by that

gentleman, and could not have been purchased of him for less than four hundred

dollars.

To return to the wolves.--These animals were in the habit of coming at

almost every hour of the night, to feed in the troughs where the offal from the

Fort was deposited for the hogs. On one occasion, a wolf killed by our party

was devoured during the night, probably by other prowlers of the same species.

The white wolves are generally fond of sitting on the tops of the

eminences, or small hills in the prairies, from which points of vantage they can

easily discover any passing object on the plain at a considerable distance.

We subjoin a few notes on wolves generally, taken from our journals, made

during our voyage up the Missouri in 1843.

These animals are extremely abundant on the Missouri river, and in the

adjacent country. On our way up that extraordinary stream, we first heard of

wolves being troublesome to the farmers who own sheep, calves, young colts, or

any other stock on which these ravenous beasts feed, at Jefferson city, the seat

of government of the State of Missouri; but to our great surprise, while there

not a black wolf was seen.

Wolves are said to feed at times, when very hard pressed by hunger, on

certain roots which they dig out of the earth with their fore-paws, scratching

like a common dog in the ground. When they have killed a Buffalo or other large

animal, they drag the remains of the carcass to a concealed spot if at hand,

then scrape out the loose soil and bury it, and often lie down on the top of the

grave they have thus made for their victim, until urged again by hunger, they

exume the body and feast upon it. Along the banks of the river, where

occasionally many Buffaloes perish, their weight and bulk preventing them from

ascending where the shore is precipitous, wolves are to be seen in considerable

numbers feeding upon the drowned Bisons.

Although extremely cunning in hiding themselves, at the report of a gun

wolves soon come forth from different quarters, and when the alarm is over, you

have only to conceal yourself, and you will soon see them advancing towards you,

giving you a fair chance of shooting them, sometimes at not more than thirty

yards distance. It is said that although they frequently pursue Buffalo, &c.,

to the river, they seldom if ever follow them after they take to the water.

Their gait and movements are precisely the same as those of the common dog and

their mode of copulating, and the number of young brought forth at a litter is

about the same. The diversity of their size and colour is quite remarkable, no

two being quite alike.

Some days while ascending the river, we saw from twelve to twenty-five

wolves; on one occasion we observed one apparently bent on crossing the river,

it swam toward our boat and was fired at, upon which it wheeled round and soon

made to the shore from which it had started.

At another time we saw a wolf attempting to climb a very steep and high

bank of clay, when, after falling back thrice, it at last reached the top and

disappeared at once. On the opposite shore another was seen lying down on a

sand bar like a dog and any one might have supposed it to be one of those

attendants on man. Mr. BELL shot at it, but too low, and the fellow scampered

off to the margin of the woods, there stopped to take a last lingering look, and

then vanished.

In hot weather when wolves go to the river, they usually walk in up to

their sides, and cool themselves while lapping the water, precisely in the

manner of a dog. They do not cry out or howl when wounded or when suddenly

surprised, but snarl, and snap their jaws together furiously. It is said when

suffering for want of food, the strongest will fall upon the young or weak ones,

and kill and eat them. Whilst prowling over the prairies (and we had many

opportunities of seeing them at such times) they travel slowly, look around them

cautiously, and will not disdain even a chance bone that may fall in their way;

they bite so voraciously at the bones thus left by the hunter that in many cases

their teeth are broken off short, and we have seen a number of specimens in

which the jaws showed several teeth to have been fractured in this way.

After a hearty meal, the wolf always lies down when he supposes himself in

a place of safety. We were told that occasionally when they had gorged

themselves, they slept so soundly that they could be approached and knocked on

the head.

The common wolf is not unfrequently met with in company with the Prairie

wolf (Canis latrans.) On the afternoon of the 13th of July, as Mr. BELL and

ourselves were returning to Fort Union, we counted eighteen wolves in one gang,

which had been satiating themselves on the carcass of a Buffalo on the river's

bank, and were returning to the bills to spend the night. Some of them had

their stomachs distended with food and appeared rather lazy.

We were assured at Fort Union that wolves had not been known to attack men

or horses in that vicinity, but they will pursue and kill mules and colts even

near a trading post, always selecting the fattest. The number of tracks or

rather paths made by the wolves from among and around the bills to that station

are almost beyond credibility, and it is curious to observe their sagacity in

choosing the shortest course and the most favourable ground in travelling.

We saw hybrids, the offspring of the wolf and the cur dog, and also their

mixed broods: some of which resemble the wolf, and others the dog. Many of the

Assiniboin Indians who visited Fort Union during our stay there, had both wolves

and their crosses with the common dog in their trains, and their dog carts (if

they may be so called) were drawn alike by both.

The natural gait of the American wolf resembles that of the Newfoundland

dog, as it ambles, moving two of its legs on the same side at a time. When

there is any appearance of danger, the wolf trots off, and generally makes for

unfrequented hilly grounds, and if pursued, gallops at a quick pace, almost

equal to that of a good horse, as the reader will perceive from the following

account. On the 16th of July 1843, whilst we were on a Buffalo hunt near the

banks of the Yellow Stone river, and all eyes were bent upon the hills and the

prairie, which is very broad, we saw a wolf about a quarter of a mile from our

encampment, and Mr. OWEN MCKENZIE was sent after it. The wolf however ran very

swiftly and was not overtaken and shot until it had ran several miles. It

dodged about in various directions, and at one time got out of sight behind the

hills. This wolf was captured, and a piece of its flesh was boiled for supper;

but as we had in the mean time caught about eighteen or twenty Cat-fish, we had

an abundant meal and did not judge for ourselves whether the wolf was good

eating or not, or if its flesh was like that of the Indian dogs, which we have

had several opportunities of tasting.

Wolves are frequently deterred from feeding on animals shot by the hunters

on the prairies, who, aware of the cautious and timid character of these

rapacious beasts, attach to the game they are obliged to leave behind them a

part of their clothing, a handkerchief, &c., or scatter gun powder around the

carcass, which the cowardly animals dare not approach although they will watch

it for hours at a time, and as soon as the hunter returns and takes out the

entrails of the game he had left thus protected, and carries off the pieces he

wishes, leaving the coarser parts for the benefit of these hungry animals, they

come forward and enjoy the feast. The hunters who occasionally assisted us when

we were at Fort Union, related numerous stratagems of this kind to which they

had resorted to keep off the wolves when on a hunt.

The wolves of the prairies form burrows, wherein they bring forth their

young, and which have more than one entrance; they produce from six to eleven at

a birth, of which there are very seldom two alike in colour. The wolf lives to

a great age and does not change its colour with increase of years.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION.

This variety of wolf is found as far north in the Arctic regions of America

as they have been traversed by man. The journals of HEARNE, FRANKLIN, SABINE,

RICHARDSON, and others, abound with accounts of their presence amid the snows of

the polar regions. They exist in the colder parts of Canada, in the Russian

possessions on the western coast of America, in Oregon, and along both sides of

the Rocky Mountains, to California on the west side and Arkansas on the east.

We examined a specimen of the White Wolf killed in Erie county, N. Y., about

forty years ago; on the Atlantic coast they do not appear; although we have seen

some specimens of a light grey colour they could not when compared with those of

Missouri, be called white wolves.

GENERAL REMARKS

Cold seems necessary to produce the Wolves of white variety. Alpine

regions from their altitudes effect the same chance. REGNARD informs us that in

Lapland, Wolves are almost all of a whitish grey colour--there are some of them

white. In Siberia, wolves assume the same colour. The Alps, on the other hand,

by their elevation, may be compared to the regions around the Rocky Mountains of

America. In both countries wolves become white. We devoted some hours to

comparing the large American, European, and Asiatic Wolves, assisted by eminent

British Naturalists, in the British Museum and the Museum of the Zoological

Society. We found specimens from the Northern and Alpine regions of both

continents bore a strong resemblance to each other in form and size, their

shades of colour differed only in different specimens from either country, and

we finally came to the conclusion that the naturalist who should be able to find

distinctive characters to separate the wolves into different species, should

have credit for more penetration than we possess.

|